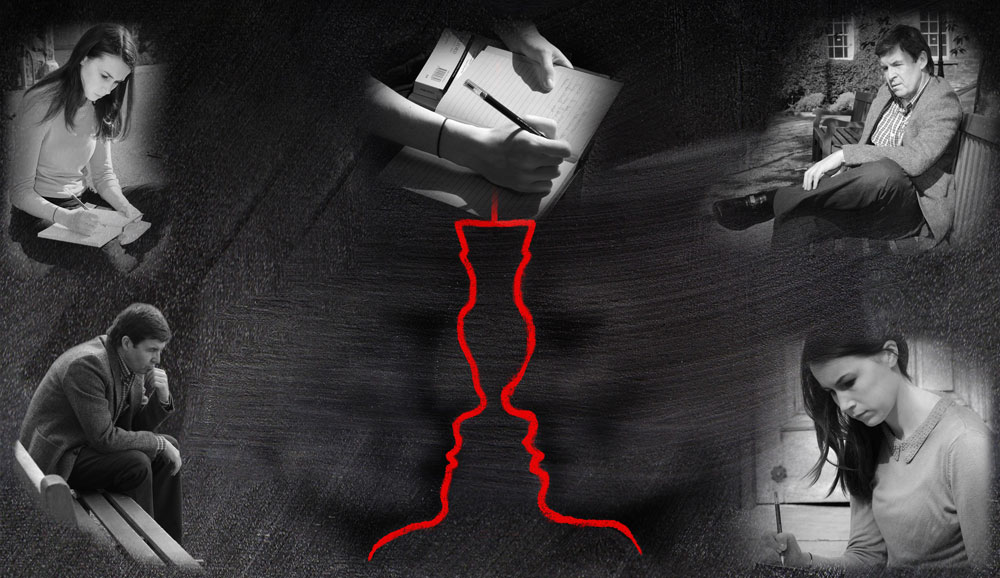

"We can only interpret the behaviour of others through the screen we create."

So says the Professor in this play, which has triggered much debate and many arguments, over its content and meaning, since it first appeared in 1992. Mamet’s superbly crafted dialogue leads to different opinions and conclusions as audiences eavesdrop on the encounter between a student and her teacher in some university.

Both share an interest in learning and education, but that’s where the common ground ends, for in some respects, they’re like chalk and cheese. All that allows Mamet to explore themes such as language and meaning, how words can cloud not clarify and be weapons of verbal warfare; how control and status are not always linked and what happens when power gets into the mix. ‘Oleanna’ is set in a supposedly utopian campus environment, where the sun doesn’t always shine and the natives aren’t always nice. The purpose and value of higher education is questioned in the dystopian world these characters inhabit. Along the way, Mamet challenges us to ponder a shadow side of political correctness as John and Carol dig themselves into a bear pit of misunderstanding — or not, depending on your point of view. For this play pulls its meaning from its audience.

Apart from enjoying a highly charged interaction between the older man and younger woman, we are left to fill in some deliberate gaps; and in so doing we may bring our own values, judgements, experiences and prejudices to bear, as we interpret what these characters do ‘through the screen we create’.

Mamet gives no information about these characters apart from what they say; and they say very little about who they are or where they’ve come from. The stage directions don’t provide any clues. The note before the opening line of the play says: ‘John is talking on the phone. Carol is seated across the desk from him’ – and that’s about as detailed as it gets. From what he says, it seems that John is a professor of education in a university somewhere; and it could be anywhere. He is critical of aspects of higher education and the assumption that it is always good and useful for everyone. Nevertheless, it is something he wants for his own son. He talks a lot about how the system is designed to make many students feel like failures. He refers to feelings throughout the play and sees negative feelings engendered by the teaching process as a hindrance to education. John is an interesting mix of traditional, conservative aspirations combined with maverick thinking and outlook.

Carol is an earnest student with a desire to know everything, but with a difficulty understanding what John teaches and how he approaches his subject. She is fastidious, a taker of copious notes and someone who sees very clear, unambiguous divisions between right and wrong, good and bad. There is little grey between her black and white perceptions. When two such minds meet, it’s as if they speak different dialects of the same language – misunderstanding and conflict are inevitable. They are endowed with intellectual abilities, but both are bereft of some of the subtleties of social interaction and emotional intelligence. Their complexities and flaws provide all the ingredients required for a fascinating, engrossing play, which Mamet described in an interview with Playboy magazine in 1995 as ‘a tragedy about power’.

It's a close-up verbal interaction between an older man and a younger woman. It is complicated by age and gender differences, but mostly by two very different ways of looking at things. The surface issues raised are compelling and very entertaining to watch, but the underlying themes are likely to linger with you long after you've left the theatre. One theme that runs through the play is the idea that 'the whole truth' is not something absolute – it is influenced by the frame of reference of the receiver. To 'help' the audience contribute to that and experience the notion first hand, Mamet does not fill in all the deliberate gaps he leaves in what we know about these characters - their background, where they are coming from - geographically, socially, politically or emotionally. He is encouraging, perhaps even provoking each member of his audience into joining the dots in their own way. Mamet's approach to presenting the play is similar to his professor's approach to guiding discovery in class. The professor tries to force his student to explore different aspects and points of view as she searches for understanding. When Carol questions John about this, he answers, ‘…that’s my job, don’t you know [...] to provoke you.’ To ears that are not at all tuned to that way of thinking, his approach is at best distracting for Carol and at worst it represents a set of 'arrogant, elitist, self-agrandising diversions'.

The approach that Mamet takes to drama in this play is what an academic like Professor John would label postmodern – that post-War questioning of previously accepted assumptions. Gone are the narratives that reinforced universal, commonly understood and agreed upon ideas that attempted to explain things and people; that conformed to religious and political models of how the world works and why we should think and behave in a certain way. In their place came stories, like ‘Oleanna’, where the writer defines him or herself as a raiser of questions and not a deliverer of answers. That job of finding answers to the questions raised is delegated to the audience. The gaps left by writers, such as Mamet, beckon an audience to get involved, to form their own opinions and derive meaning.

With two characters, a man and a woman, a teacher and his student, there are three broad responses to a conflict between them: he was wrong, she was wrong or they are both right and wrong at different times throughout the play. The latter seems to have been Mamet's intention, based on what he has said in interviews about John and Carol. Regardless of where your judgement takes you, this play is about power exercised by two individuals, not in the relatively public forum of a lecture theatre or seminar room, but in a private meeting between a young student and her teacher in his office. What follows focuses attention on what is said viewed through the lens of political correctness; questions the appropriateness of the behaviour that accompanies it; and leads to an ending in Act 3 that few would expect from Act 1.

If you haven’t seen the play, let’s not spoil it by saying anything more than that, or talking specifically about some of the issues that caused most controversy. You’ll draw your own conclusions and they are quite likely to be different to those of the person sitting next to you. One of the most interesting things about this play is that it’s about much more than what hits you at first. Underneath the surface drama, which is compelling and highly entertaining, this play about the use and abuse of power regardless of status has some interesting things to say about communication and language. It shows how understanding between two people depends so much on having a shared frame of reference, similar attitudes or an ability and willingness to see things through another's eyes. Ultimately it’s about language, how it forms and filters thought, and how meaning is in the hands of he or she who is in a position to control its interpretation.

All that makes for great discussion, debate and even the odd argument when different people see the same things from different points of view. What’s equally great is that this play offers a thoroughly enjoyable evening as these two characters do just that.

Declan Brennan - October 2013

The title Oleanna does not refer directly to anything or anyone in the play - it is never mentioned in the dialogue. So, what is this obscure reference all about? The name 'Oleana' (spelt with one ‘n’) was a nineteenth-century utopian community in Pennsylvania named after its founder, Ole Bull (1810-1880) and his mother Anna. He was a famous Norwegian virtuoso violinist whose musical talent and prowess was up there with the likes of Paganini. After a very successful tour of the USA in 1852, he purchased 11,000 acres of land in Potter County, Pennsylvania and invited fellow Norwegian immigrants to settle there with him. However most of the land proved to be barren and the dream of an idyllic, utopian community failed.

The failure inspired a satirical Norwegian folk-song called ‘Oleanna’ (spelt with two ‘n’s), which was later translated into English and recorded by Pete Seeger. Mamet included the first verse of the song in the printed version of the play.

Oh to be in Oleanna,

That's where I'd like to be

Than to be in Norway

And bear the chains of slavery.

Perhaps the most likely connections between this and the play are the purchase of land and the ideal, real or imagined, of living and working closeted in the perfection of a utopian environment set apart from the rest of the world. In the play, John spends time on the phone to his wife or his lawyer talking about the purchase of a new house. And both characters debate the nature and value of higher education, which might be seen either as a universal right, or as an elitist institution which reinforces privileged groups in society.

When this obscure allusion to Ole Bull and his mother Anna is linked to John’s wrestling with issues around the sale of land and his discussions with Carol, you might think that Mamet could have ended the play with the professor saying something like ‘Oh to be in Oleanna, before the bubble burst' - without giving anything away, he doesn't ... well, not really.